Back استرواح الصدر Arabic Pnevmotoraks Azerbaijani Пневмоторакс Bulgarian Pneumotòrax Catalan Pneumotorax Czech Pneumothorax German Πνευμοθώρακας Greek Pneŭmotorako Esperanto Neumotórax Spanish Pneumotorax Basque

| Pneumothorax | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Collapsed lung[1] |

| |

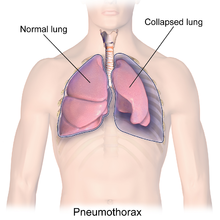

| Illustration depicting a collapsed lung or pneumothorax | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology, thoracic surgery |

| Symptoms | Chest pain, shortness of breath, tiredness[2] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[3] |

| Causes | Unknown, trauma[3] |

| Risk factors | COPD, tuberculosis, smog, smoking[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Chest X-ray, ultrasound, CT scan[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Lung bullae,[3] hemothorax[2] |

| Prevention | Smoking cessation[3] |

| Treatment | conservative, needle aspiration, chest tube, pleurodesis[3] |

| Frequency | 20 per 100,000 per year[3][5] |

A pneumothorax is an abnormal collection of air in the pleural space between the lung and the chest wall.[3] Symptoms typically include sudden onset of sharp, one-sided chest pain and shortness of breath.[2] In a minority of cases, a one-way valve is formed by an area of damaged tissue, and the amount of air in the space between chest wall and lungs increases; this is called a tension pneumothorax.[3] This can cause a steadily worsening oxygen shortage and low blood pressure. This leads to a type of shock called obstructive shock, which can be fatal unless reversed.[3] Very rarely, both lungs may be affected by a pneumothorax.[6] It is often called a "collapsed lung", although that term may also refer to atelectasis.[1]

A primary spontaneous pneumothorax is one that occurs without an apparent cause and in the absence of significant lung disease.[3] A secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in the presence of existing lung disease.[3][7] Smoking increases the risk of primary spontaneous pneumothorax, while the main underlying causes for secondary pneumothorax are COPD, asthma, and tuberculosis.[3][4] A traumatic pneumothorax can develop from physical trauma to the chest (including a blast injury) or from a complication of a healthcare intervention.[8][9]

Diagnosis of a pneumothorax by physical examination alone can be difficult (particularly in smaller pneumothoraces).[10] A chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT) scan, or ultrasound is usually used to confirm its presence.[5] Other conditions that can result in similar symptoms include a hemothorax (buildup of blood in the pleural space), pulmonary embolism, and heart attack.[2][11] A large bulla may look similar on a chest X-ray.[3]

A small spontaneous pneumothorax will typically resolve without treatment and requires only monitoring.[3] This approach may be most appropriate in people who have no underlying lung disease.[3] In a larger pneumothorax, or if there is shortness of breath, the air may be removed with a syringe or a chest tube connected to a one-way valve system.[3] Occasionally, surgery may be required if tube drainage is unsuccessful, or as a preventive measure, if there have been repeated episodes.[3] The surgical treatments usually involve pleurodesis (in which the layers of pleura are induced to stick together) or pleurectomy (the surgical removal of pleural membranes).[3] About 17–23 cases of pneumothorax occur per 100,000 people per year.[3][5] They are more common in men than women.[3]

- ^ a b Orenstein DM (2004). Cystic Fibrosis: A Guide for Patient and Family. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 62. ISBN 9780781741521. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Pleurisy and Other Pleural Disorders". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Bintcliffe O, Maskell N (May 2014). "Spontaneous pneumothorax". BMJ. 348: g2928. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2928. PMID 24812003. S2CID 32575512.

- ^ a b "What Causes Pleurisy and Other Pleural Disorders?". NHLBI. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d Chen L, Zhang Z (August 2015). "Bedside ultrasonography for diagnosis of pneumothorax". Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery. 5 (4): 618–623. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2015.05.04. PMC 4559988. PMID 26435925.

- ^ Morjaria JB, Lakshminarayana UB, Liu-Shiu-Cheong P, Kastelik JA (November 2014). "Pneumothorax: a tale of pain or spontaneity". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 5 (6): 269–273. doi:10.1177/2040622314551549. PMC 4205574. PMID 25364493.

- ^ Weinberger S, Cockrill B, Mandel J (2019). Principles of Pulmonary Medicine (7th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 215–216. ISBN 9780323523714.

- ^ Slade M (December 2014). "Management of pneumothorax and prolonged air leak". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 35 (6): 706–714. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1395502. PMID 25463161. S2CID 35518356.

- ^ Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, Pons PT, Cantrill SV (August 2009). "Blast injuries". Lancet. 374 (9687): 405–415. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60257-9. PMID 19631372. S2CID 13746434.

- ^ Yarmus L, Feller-Kopman D (April 2012). "Pneumothorax in the critically ill patient". Chest. 141 (4): 1098–1105. doi:10.1378/chest.11-1691. PMID 22474153. S2CID 207386345.

- ^ Peters JR, Egan D, Mick NW (2006). Nadel ES (ed.). Blueprints Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 44. ISBN 9781405104616. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search